Editor's note: This article was originally written for the Waterfront Preservation Alliance of Greenpoint and Williamsburg. Other than some light editing and formatting, it is reprinted here in its original form.

If you take the J/M/Z, you will recognize St. Paul German Evangelical Lutheran Church immediately (particularly if you wait for the train at the Marcy Avenue stop). Theology aside, St. Paul's has a lot in common with Holy Trinity: both were founded as German congregations; both are among the oldest congregations in Williamsburg; both buildings date to the 1880s; and both buildings were designed by prominent New York City architects. At St. Paul, the architect was J. C. Cady (who designed the American Museum of Natural History, among many others). And in this case, the architect was responsible for the entire complex of buildings - church, rectory and parish house.

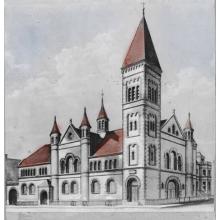

St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church is located on the corner of South Fifth Street and Rodney (formerly Ninth) Street in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. The complex of buildings, which includes the Church, Sunday School and Parsonage, were constructed in 1884-85 to the designs of J. C. Cady & Company. The buildings were designed in the Romanesque style and constructed of Holland and Philadelphia brick with terra cotta and brownstone trim.

Founded in 1853, the Church is one of the oldest German Lutheran congregations in North Brooklyn, and reflects the dominance of German immigrants in the neighborhood in the latter half of the nineteenth century. St. Paul counted among its congregants many leaders of Williamsburgh’s German immigrant community, including sugar barons and merchants. In a reflection of the chaotic religious schisms of the mid-nineteenth century, many of Williamsburgh’s other Evangelical Lutheran churches traced their roots to St. Paul’s.

The St. Paul’s complex consists of three buildings - the Church, a Sunday School and Chapel to the east on South Fifth Street, and a Parsonage to the south on Rodney Street. The entire complex is constructed of Holland and Philadelphia brick, with terra cotta and brownstone trim. The most prominent element on the church is a 135’ bell tower located at the corner of South Fifth and Rodney. To the south (right) of the bell tower is the main entrance to the church. The front facade of the church is dominated by a massive Romanesque arch at the ground-floor story, which serves as the main entrance. Above the entrance is a large arched window with smaller arched windows flanking it. The transept windows on South Fifth Street are in a similar configuration, with two smaller arched windows at the first story below. All of the arched windows at the front of the church and at the transept have leaded stained glass.

To the south of the Church on Rodney Street is the Parsonage, which is three stories tall, with a mansard roof forming the third story, on a raised basement. The Parsonage is two bays wide, with the southernmost bay a projecting oriel for two stories. The Church and Parsonage are separated by a semi-detached circular tower, which also served as a ventilation flue.

To the east of the transept on South Fifth Street is a second monumental arch set into a projecting porch, which serves the chapel and Sunday School. The transept is flanked by semi-detached circular towers which also served as ventilation flues. To the east of the Sunday School is a third monumental arched opening which leads to a parking lot beyond.

The three St. Paul’s buildings are distinguished by their robust and intricate brickwork, which is some of the finest of its period. The masonry is generally in fair to good condition, with significant soiling. The pointing is failing in selected areas. The roofs appear to retain their original copper flashing, although the roofs themselves have been replaced and original details are missing. The main entry doors to the church have been replaced with aluminum doors, but the historic transom remains in place above these doors. The door to the Parsonage has been replaced with an unarticulated hollow-metal door. The remaining doors to the complex appear to be historic.

Church History

St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church was founded in 1852. Although it was preceded by at least one Lutheran congregation (St. John’s, which was originally located at Graham Avenue and Ten Eyck Street), St. Paul’s now counts itself as the oldest Lutheran church in Williamsburg. In June of 1852, the Church purchased two lots at the southeast corner of South First Street and Rodney Street, and immediately began construction of a new masonry church. The church’s first pastor, E. F. Schlueter, was appointed in March of 1853. The new building was dedicated in May of 1853, about the time that the congregation officially organized itself as St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church.

The first quarter century of the church’s history was tumultuous. There was a high turnover among the pastors, many of whom left to form rival congregations within the neighborhood. The schisms were the result of synodical disagreements, disagreements over language (English vs. German) and other issues common to many Protestant denominations of the time. Among the churches founded by former pastors of St. Paul’s were Zion Evangelical Church on Henry Street (1856), St. Matthew’s German Evangelical Lutheran Church on North Fifth Street (1864), St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in Greenpoint (1867), Emanuel’s Evangelical Lutheran Church at South First and Marcy (1874), and Grace Evangelical Lutheran Church at Rodney between South First and South Second (1882).

Meanwhile, faced with overcrowding at its South First Street church, St. Paul’s began looking for new accommodations as early as 1870. In the Spring of 1873 the church purchased the properties at the corner of South Fifth and Rodney. Financial woes, which had always plagued the congregation, prevented it from starting work on the new church until the Summer of 1884. Ground was broken on the new church on 2 August 1884, and the cornerstone was laid the following 12 October. The Parsonage was completed in June, 1885 and the Sunday School in September of the same year. Finally, on 11 October 1885, the new church was dedicated.

J. C. Cady

Architect Josiah Cleaveland Cady was born in Providence, Rhode Island in 1837. He spent most of his career practicing in New York City, and died there in 1919. His best known work is the south wing of the Museum of Natural History, which he designed with partner Milton See. With his own firm J. C. Cady & Co., he was the architect of the original Metropolitan Opera House on Broadway between 39th and 40th Streets (1883), the former Brooklyn Public Library (1890) and German Evangelical Lutheran Church (1888) on Schermerhorn Street, the former New York Avenue Methodist Church in Crown Heights (1892), the former St. Andrew’s Methodist Episcopal Church on West 76th Street (1889) and the United Presbyterian Church of the Covenant on East 42nd Street (1871). His later partnership, Cady, Berg & See also designed numerous churches and collegiate buildings, including buildings at Yale University, Trinity College, Williams College and Wesleyan University.

History and Geography of Williamsburgh and Its German Populace

The area of Brooklyn that is today called Williamsburg (without an “h”) was, together with Greenpoint, in Colonial times part of the town of Bushwick. One of the five original Colonial-era towns of Kings County (together with Brooklyn, Flatbush, New Utrecht and Gravesend), the Town of Bushwick was first settled by French émigrés. The center of the Town of Bushwick, such as it was, was located about a mile northeast of St. Paul’s, near the intersection of what is now Metropolitan Avenue and Bushwick Avenue.

Growth was slow throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, and even in the early part of the 19th century. In 1802, Woodhull bought much of the land between the Brooklyn border (at today’s Division Avenue) and the Bushwick Inlet. It was on this tract of land, bordered on the east by Bushwick Creek (roughly where Union Avenue runs today), that Woodhull proposed to establish a new village. In 1802, Woodhull hired Colonel Jonathan Williams to lay out the streets and avenues of his proposed development. It was in honor of Colonel Williams that Williamsburgh (with an “h”) got its name.

In 1827, Williamsburgh was incorporated as a separate village within the Town of Bushwick. In 1852, Williamsburgh was declared a city in its own right. In the preceding decades, Williamsburgh had grown from a small village to (in 1830) a town separate from Bushwick, and then to a city. Along the way, the population of Williamsburgh had grown from 934 in 1820 to 1,117 in 1830 to 5,094 in 1840. By the time it was declared a city in 1852, the population of Williamsburgh was estimated at 38,000, making it one of the larger cities in New York State.

To a great degree, Williamsburgh’s growth and prosperity can be traced to the wave of German immigration that began in the late 1840s. German immigrants quickly established themselves as the dominant ethnic group in much of east Williamsburgh and Bushwick. The Germans were very active in industry - in particular sugar refining and brewing - and in the banking and insurance sector. St. Paul’s counted among its leaders and parishioners many of the most prominent and successful German residents of Williamsburg. These included three prominent sugar refiners, Luer Wintjen, Jost Moller and Claus Doscher, and a large number of merchants. Most of the sugar refineries were located on the Williamsburgh waterfront, while the breweries were for the most part located in east Williamsburg and Bushwick. With the increase in the German populace came an increase in German cultural and social institutions. These included Turn halls, singing societies, beer gardens, social halls, and, of course, churches.

The Germans continued to be a dominant presence in Williamsburg until the early years of the 20th century, when (in a pattern similar to that seen in lower Manhattan) subsequent generations began to disperse. By the first decade of the 20th century, much of the western portion of Williamsburg south of Grand Street was occupied by Jewish immigrants. In the 1930s and later a second demographic change began to take shape with the migration of Puerto Ricans to Williamsburg.

As Williamsburg’s population began to change, so too did its geography. The first major disruption to the neighborhood came with the opening of the Williamsburg bridge in 1903. The bridge itself divided the south side of Williamsburg and resulted in the demolition of a number of major churches along South 5th Street. The construction of the Williamsburg Bridge Plaza also created a void in the center of the south side. To the west of the plaza, many rowhouses, churches and other buildings were demolished to construct tenements for the new wave of Jewish residents coming from the Lower East Side. In the 1930s, Williamsburg Houses, the first of a series of public housing developments (and a New York City Landmark), was constructed in east Williamsburg. In later years, many blocks of south Williamsburg would be razed to construct subsequent housing developments.

The most significant disruption to the fabric of the neighborhood came with the construction of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway in the 1950s. This artery literally divided the neighborhood, and its construction remains a point of contention with residents to this day. Ironically, the grand views of St. Paul’s Church that we see today are a direct result of the construction of the BQE, which, if it had been routed a block to the east, would have resulted in the demolition of the church itself.