The most distinctive feature of Teddy’s Bar at 96 Berry Street is the projecting wood and sheet-copper corner storefront with a beautiful decorative-glass transom reading “Peter Doelger’s Extra Beer”. Portions of the storefront were rebuilt after a car crashed into it about 10 years ago, but most of it – and all of the decorative glass - dates to at least 1907. That stained-glass transom is the source of much of the mythology that surrounds 96 Berry, tying it to a 19th-century beer baron and a 20th-century Hollywood icon. The odds that either ever set eyes on the building are practically nil.

What actually happened at 96 Berry Street is far less glamorous than movie stars and beer barons, but it tells the story of Williamsburg and Brooklyn in the decades surrounding the turn of the 20th century, one of shifting populations and changing capitalist landscapes. And at the very least, this story is true.

The Brief History

First, some basic facts to get out of the way. 96 Berry Street, at the northwest corner of North 8th Street, is a largely intact neo-Grec tenement dating to the 1880s. The building itself is relatively simple, with lovely neo-Grec details, including distinctive header-brick stringcourses above each floor, and the very typical stone sill courses and shouldered lintel courses that characterize the style.

The building was constructed in 1885 at a cost of $11,000, designed by architect A. Herbert for Frederick Mesloh.1 Herbert was a prolific, if not very inventive, architect in the Eastern District of Brooklyn. Most of his work was designing tenements and flat houses, and he was responsible for hundreds (if not thousands) of them. Mesloh was a local milk dealer, and this appears to be his only real estate venture. Mesloh and his family lived at 96 Berry from 1885 to 1907, and for at least part of that time Mesloh operated his milk business out of the one-story rear extension at 117 North 8th Street.2

James Walsh & Peter Doelger

Prohibition years aside, 96 Berry Street has always housed a bar on the ground floor. The first establishment recorded at 96 Berry was Matthew Smith’s “liquors".3 In the 1889 directory, Smith is listed as a supervisor for the 14th Ward and operator of saloons at 96 Berry and down the block at 129 North 8th Street. Smith lived further east on North 8th Street, at number 143.4 At this time (late 1880s), Bernard Reilly operated saloons at various locations in the neighborhood5, and by 1892, he was operating the saloon at 96 Berry Street6. Reilly appears as the proprietor of the saloon at 96 Berry through at least April of 1899, and in October of that year, James J. Walsh is the proprietor.7

Record of Reilly’s and Walsh’s saloons can be found in directories, but also in a series of chattel mortgages each gave to different brewers. Reilly carried a $1,400 loan from brewer Otto Huber from 1892 to 1899, and Walsh owed $1,200 to brewer L. Eppig from 1899 to at least 1905. Such debts were common at the time, with brewers providing saloon equipment (chattel) on credit. In exchange for favorable (and apparently easily renewable) terms, the saloons not only paid interest but also bought their beer exclusively from the brewery. Eppig’s and Huber’s breweries were both Bushwick-based operations, and this pattern of saloons working on credit from local breweries was emblematic of local control of the beer trade in the 19th century. Beer was still a somewhat perishable commodity, brewed and consumed locally.

This system of chattel mortgages and chattel liens on saloon equipment was very common in the late 19th century. But a new trend was emerging at the turn of the century, as brewers (especially) began branching out into the real estate field, buying up buildings for their desirable locations and existing saloons, and even developing new buildings with saloons and rental apartments above.

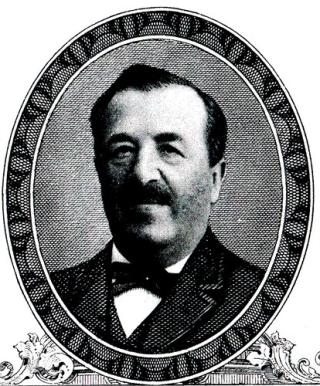

Photo: findagrave.com

This is what happened in 1907, when 96 Berry was bought by Peter Doelger8, a Manhattan-based brewer who was aggressively expanding his territory to Williamsburg and Greenpoint. During this period Doelger bought dozens buildings In the area, most of them corner properties and all with a saloon on the ground floor. Bushwick brewer Otto Huber was doing much the same thing in these years, as were other brewers. These were real estate investments, but they were also business investments. Rather than rely on saloon operators, who went in and out of business or defaulted on their loans, the brewers could control their own leases and ensure that their products alone were sold.

It is likely that the storefront and copper cornice at 96 Berry, and certainly the stained glass, date to 1907 and were installed by the brewery when it bought the building and became the sole supplier to Walsh’s saloon. The man who is memorialized in stained glass and whose name was on the deed is Peter Doelger, Sr. (1832-1912), a German immigrant who arrived in the United States in 1848, settling in Manhattan’s Kleinedeutschland neighborhood (today’s East Village). Peter initially worked at his brother Joseph’s brewery, which was located on East 3rd Street, buy by 1859 he had opened his own brewery also in the East Village. Following the Civil War, Peter expanded to a full-block site uptown in Turtle Bay, and by 1895, Peter Doelger’s Brewery was the 11th largest in the nation.9

While the Doelger real estate purchases were made in the name of the elder Peter Doelger, the expansion and investments appear to have been undertaken by his son Peter Doelger, Jr., who was increasingly running the family business during this period and actively expanding the brewery’s market beyond Manhattan as well as diversifying its portfolio into real estate. While Peter, Jr. was probably involved in the acquisition and some level of the real estate operations of 96 Berry, it is not likely that his father, who was 75 years old in 1907 and comfortably ensconced in a mansion at Riverside Drive and West 100th Street, ever set eyes on the place. Nor Is It likely that the Doelger’s took an active role In the operation of the saloon at 96 Berry - that remained In the hands of James Walsh for years to come.

Over the years, the Doelgers bought many buildings in north Brooklyn. On his death in 1912, these properties were transferred from Peter Doelger’s estate to the corporate entity Peter Doelger Brewing Company. On two days in July of 1913, 20 such properties In north Brooklyn were transferred en masse10, an indication of the scope of Doelger’s real estate operations.

What About Mae West?

The greatest myth surrounding 96 Berry is that of actress Mae West. Various accounts claim that West was the niece of Peter Doelger, that she was born (or lived) upstairs at 96 Berry, or that her father, Jack West, was a bartender at 96 Berry. None of that appears to be true.

The origins of these myths are twofold. Mae West herself claimed to be related to Peter Doelger, insisting that her maternal grandfather, Jacob Delker, was a cousin of Peter Doelger (allegedly, Delker was a bastardization of Doelger, assigned by an immigration officer at Castle Clinton).11 There is no evidence of a relationship between Jacob Delker and Peter Doelger (or any other Doelger) anywhere in the historic record.12 The only contemporary assertion for this comes from Mae West herself, and even her biographers seem skeptical of the claim (as they are of claims that her maternal grandmother was Jewish (she was Lutheran) or that her paternal grandfather was a light-skinned African American (he was from England by way of Newfoundland).13 And although they shared German ancestry, the Doelgers and Delker appear to have been from different social, geographic and cultural spheres there, with the former being Bavarian Catholics, the latter Lutherans from Würtemberg.

Mae West was the originator of, and deeply invested in, her own mythology. Her own embellished biography has, with time, been further exaggerated by others. These exaggerations were abetted by the fact that Peter Doelger and Jacob Delker both had daughters named Mathilda, both of whom were about the same age. This coincidence has led some to claim that Peter Doelger was the father of Mae’s mother, Tillie (Mathilda) Delker. Legend has it that Peter was furious at the idea of Tillie marrying “Battling Jack" West, an Irish boxer and local Greenpoint enforcer (whose own biography seems to have been embellished by his daughter). In this telling, Mathilda Doelger/Delker left Jack West and married another beer scion in the mid-1890s. But the fact is that Tillie Delker and Jack West remained married (happily, we hope) for 41 years.

Mae West never claimed to have lived in or set foot in 96 Berry. That part of the myth seems to originate with the “Peter Doelger’s Extra Beer” stained glass at 96 Berry and the idea that Peter Doelger himself ran the place. This leap of faith probably stems from the fact that 96 Berry is the last surviving “Doelger” branded saloon.

One legend says that Jack West, Mae’s father, tended bar at 96 Berry, the recipient of his father-in-law’s charity. In fact, the Doelgers never ran (or owned) the saloon at 96 Berry. They owned the building, but until it was shut down for prohibition in 1920, the saloon at the corner of North 8th and Berry was operated by James J. Walsh. The Doelgers were just the landlords (and beer suppliers). Walsh was not even exclusive - he also ran a saloon at 125 Bedford, on the corner of North 10th Street, in a building that he, not the Doelgers, owned.14

The other legend associated with 96 Berry is that it was the birthplace or residence of Mae West. Mae West was 14 years old and already established in vaudeville when Peter Doelger bought 96 Berry in 1907, so the Doelger connection clearly has nothing to do with where she was born (probably in her grandparents Bushwick home). And while the Wests moved about a lot (as did most working-class people in this era), primarily in East Williamsburg and Bushwick15, there is no record of them living at 96 Berry. (Mae’s grandfather lived at 131 Meeker Avenue for many years, but there Is very little to tie her Immediate family to Greenpoint - her “Greenpoint” roots may have been another of Mae West’s embellishments.)

Who Did Live at 96 Berry?

So if Mae West, Peter Doelger and their families never lived at 96 Berry Street, who did? The usual suspects, one might say. “Tenement” was a catch-all phrase in the late 19th century, which typically meant multi-family apartment for working-class to middle-class residents. 96 Berry fit nicely into this definition. Its owner (Frederick Mesloh) was a local merchant who lived and worked on premises - buying a tenement was a step up into the bourgeoisie for many immigrants in the 19th century, especially those in the merchant class. The earliest recorded tenant (in 188916) was a boat pilot by the name of Thomas Butler17. In 1897, the tenants included a cooper (Joseph Brennan), a painter (James Cunningham) and a deckhand (Thomas Loftus).18 Not all of the tenants were working class - local Alderman Edward Scott resided there in the late 1890s.19

The 1900 census (the first in which the building appears) records 36 people in six families living at 96 Berry. In addition to the Mesloh family (Frederick, his wife Gazinia (or Eliza) and their 6 children), James Walsh, his wife Catherine and their two children lived above their saloon. James Conigsland20 (janitor) and his wife Lizzie, Henry Hahn (machinist) and his wife Margaret, Thomas Loftus (now a brakeman) and his wife Mary, and James Dorgan (truck driver) and his wife Ellen rounded out the tenants. Four of the six families were of Irish descent, two German, and the parents in four of the families were born abroad. But of the 25 children living at 96 Berry, only one, Henry Hahn, Jr., was born abroad; the other 24 were all born in New York state.21 Accommodations were typically cramped for the time - at two apartments per floor, these were generous by tenement standards but by no means spacious suites, and with an average family size of 6 persons quarters must have been tight. On the other hand, unlike many families, none of the residents of 96 Berry needed to bring In boarders, Indicating a stability within the working class.

The 1905 New York State census shows a similar array of families. The Meslohs, Walshes, Cunninghams (Conigslands) and Dorgans are all still in residence. They are joined by John and Dina Michael, German immigrants with one child, and Joseph and Babet Hren [sic?], respectively from Austria and Bavaria, and their two children. In all 35 people lived in the building in 1905. By this time, many of the older children had jobs of their own, ranging from nurse to apprentices in shoe factory to a sugar tester and a nickel polisher.22

Frederick Masloh probably died in early 1907. His name continues to appear in directories through 1908, but the sale of the building in July of 1907 was conducted in the name of his eldest son, John H. F. Mesloh.23 James Walsh continued to run the saloon in the building, but by the 1910 U.S. census, he and his family were living at 125 Bedford Avenue (a building that he owned).24 There were seven families living in 6 apartments at 96 Berry in 1910, all of them renters. Ellen Dorgan, Christina (Dina) Michael and Elizabeth Conigsland (Cunningham) are all listed as widows (Dorgan appears to be living alone). New additions since 1905 are Dorrand and Leslie Palermo, John and Alice Nelson, Henry Hughes, Antoinette Kotcher and Cornelius and Mary McErlain.25

Starting with the 1915 census, the demographics of the neighborhood begin to shift with an influx of Eastern European immigrants. These changes bear out at 96 Berry, where three of the six families are now Russian emigres (some may have been Russian Poles, as parts of Poland were under Russian control until 1918), while the other three families were US born (the Michael, Conigsland and Dorgan families).26

1915 finds James Walsh still living at 125 Bedford27, and directories through at least 1920 show that he operated bars at 96 Berry, 125 Bedford and possibly 111 Jackson Avenue in Long Island City. Walsh was successful enough that by 1920 he was able to move to East 21st Street in Midwood, in what was probably a brand new house in a newly developed block of single-family houses. Walsh’s move represents a shift in housing that was taking place in this period, as streetcar suburbs began emerging as the new ideal for middle-class housing.

Of course, another cultural shift was also about to hit Walsh – prohibition. The Eighteenth Amendment, which went into effect on January 17, 1920, had a tremendous impact on North Brooklyn, shutting down most of its breweries and saloons and driving drinking (and German culture) underground. It is not clear what happened to Teddy’s during prohibition – did it become a restaurant, a speakeasy, or just a vacant space? The 1920 census (enumerated in April, 1920) still lists James Walsh as the proprietor of a saloon, and the 1920 Brooklyn telephone directory lists Walsh as the owner of saloons at 125 Bedford and 111 Jackson, but not at 96 Berry. Eventually, Walsh did leave the saloon life and became a real estate broker, a job he held through 1940.

Through the coming years, the residents of 96 Berry were increasingly from Eastern Europe. In 1920, three families were Polish and two German. By 1930, all of the residents were from Eastern Europe – Czechoslovakia, Poland and Ukraine). In 1940, 38 people lived at 96 Berry, two families from Czechoslovakia, two from Poland, one from Austria and one a mixed Ukranian-Polish family.

Over the course of the 60-plus years following Its construction In 1885, dozens of families lived and worked at 96 Berry. None of them were Wests, and none were Doelgers. Most of them were first- or second-generation working-class immigrants. From the time of its construction by a German milk dealer, through the operation of an Irish saloon and to it post-Depression dominance by Eastern Europeans, the population of 96 Berry mirrored that of the city and reflected the working-class roots of north Williamsburg. Putting aside myth and fantasy, the story of 96 Berry is a rich tale of Williamsburg, Brooklyn and New York City.

- 1“Buildings Projected,” Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide 36, no. 903 (July 4, 1885), 774.

- 2Lain’s Brooklyn Directory for the Year Ending May 1, 1889 (Brooklyn, N.Y.: Lain & Company, 1889), 813, https://archive.org/details/1889BPL.

- 3Lain’s Brooklyn Directory for the Year Ending May 1, 1887 (Brooklyn, N.Y.: Lain & Company, 1887), 1077, https://archive.org/details/1887BPL.

- 4Lain’s Brooklyn Directory for the Year Ending May 1, 1887, 1077.

- 5Lain’s Brooklyn Directory for the Year Ending May 1, 1887, 949; Lain’s Brooklyn Directory for the Year Ending May 1, 1889, 990.

- 6“Chattels: Saloon and Restaurant Fixtures,” Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide, v. 49, no. 1256 (April 9, 1892), 592. Chattel mortgage from B. Reilly to Otto Huber. This was the first mortgage given by Reilly at this address, indicating that 1892 was probably the year that Reilly started operating at 96 Berry.

- 7“Chattels: Saloon and Restaurant Fixtures,” Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide, v. 63, no. 1616 (March 4, 1899), 398.; “Chattels: Saloon and Restaurant Fixtures,” Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide, v. 64, no. 1648 (October 14, 1899), 584. Walsh is also listed as a resident in the 1900 U.S. Census (see below). A listing of liquor licenses for 1898 lists a license at 96 Berry under the name of Matthew (not James) Walsh; Reilly is not listed in this document (digital copy of document; original source unknown).

- 8“Conveyances,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 3, 1907, 15. The sale to Doelger was done through a same-day third-party flip - John H. F. Meslob [sic], son of Frederick, sold the property to August D. F. Meyer on July 2, 1907; that same day, Meyer flipped the property to Doelger.

- 9Gregg Smith, “The Doelger Breweries,” Realbeer.com, accessed November 17, 2018, http://www.realbeer.com/library/authors/smith-g/doelger_ny.php.

- 10“Conveyances,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 22, 1913; “Conveyances,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 28, 1913. Throughout 1913, dozens of similar transactions took place in Manhattan, Queens and the Bronx, but the transactions cited here seem to be the only ones for Brooklyn.

- 11Jill Watts, Mae West: An Icon in Black and White (Oxford University Press, 2003), 7.

- 12Mae West NYC, "Mae West: Delker Not Doelger," Mae West (blog), August 20, 2011, http://maewest.blogspot.com/2011/08/mae-west-delker-not-doelger.html.

- 13Watts, Mae West, 4, 7.

- 14The 1910 census records Walsh as the owner of 125 Bedford. Directories from 1909 through 1920 list Walsh’s liquors at both 96 Berry and 125 Bedford. Based on directory searches, James Walsh may have been the proprietor of a third saloon at 111 Jackson Avenue in Hunters Point.

- 15Jack West and family are recorded at 308 Humboldt Street in 1899; 137 Conselyea Street in 1900; 140 St. Nicholas Avenue in 1905; and 421 Stanhope Street in 1910.

- 16At the time of construction, the building address was 385 or 385 Third Street. Right around this time the street name changed from Third Street to Berry Street, and shortly thereafter the street numbering changed. This, and the fact that people moved frequently, means that early directory show few hits for this building.

- 17Lain’s Brooklyn Directory for the Year Ending May 1, 1889, 155.

- 18Lain & Healy’s Brooklyn Directory for the Year Ending May 1, 1897 (Lain and Healy, 1897), http://archive.org/details/1897BPL.

- 19“Alderman Scott Ill,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 1, 1898.

- 20Recorded in other years as James Cunningham.

- 21“United States Census, 1900”, Kings County, Ward 14, ED 206, p. 4 (National Archives and Records Administration, 1900), https://www.ancestry.com.

- 22“New York State Census, 1905”, Kings County, Ward 14, AD 12, page 1 (State of New York, 1905), https://www.ancestry.com.

- 23“Conveyances,” July 3, 1907.

- 24“United States Census, 1910”, Kings County, Ward 14, ED 280, page 24 (National Archives and Records Administration, 1910), https://www.ancestry.com

- 25“United States Census, 1910”, Kings County, Ward 14, ED 278, page 13.

- 26“New York State Census, 1915” (State of New York, 1915), Ward 14, ED 13, page 4, https://www.ancestry.com.

- 27“New York State Census, 1915”, Ward 14, ED 15, page 5.